[Vung Tau, 2/18/25]

When I posted a photo of the free library in Phước Bửu (pop 18,000), “Tim” commented, “Public library? Very interesting, because this thing is not in their culture—not at all.” So sure!

I replied, “There are free to use libraries everywhere. Of course, books that knock the Party or Uncle Ho aren't available, but there's enough quality literature to keep readers happy. You don't need a card to enter, only to borrow. Vietnam’s oldest public library dates to 1868.”

Reviewing Apocalypse Now Redux in 2001, I noted:

As Willard’s boat travels up the Nung river, the only signs of civilisation are two US army bases and, in the new extended version, a French plantation. This has nothing to do with the Vietnam of reality. As anyone who has been there will tell you, Vietnam is (and was during the war) grossly overpopulated. Rivers and roads are lined with settlements. The US, by comparison, is more wild. Another thing a visitor to Vietnam can readily see is the ubiquity of the written language—that is, of civilisation. Signs and banners are everywhere. None of this is apparent in any of the panoramic shots of Apocalypse Now. Coppola hasn’t just withheld speech from the Vietnamese, he has also banned them from writing.

It’s not just about Vietnam, it is Vietnam, crowed Coppola. In his Vietnam, Viets are language free, so of course there are no libraries or bookstores.

In 1865, Trương Vĩnh Ký (1837-1898) founded the first Vietnamese newspaper in Latinized script. No common rag, it included poems, scholarly articles, essays and translations from Western languages and Chinese. Fluent in five or six languages, Trương Vĩnh Ký could read many more. Published in Saigon, Gia Định báo was distributed for free, primarily at schools. A tireless promoter of Vietnamese civilization, Trương Vĩnh Ký authored Cours d’histoire annamite, Cours de littérature annamite, Guide de la conversation annamite and Les convenances et les civilités annamites, etc. A barbarian like Coppola could certainly use the last to learn Vietnamese manners.

Before 1975, the best Saigon bookstore was Khai Trí. Founded in 1952, it was only shut down after Communist tanks rolled into the city. Sixty tons of books were destroyed. In 1976, its 51-year-old owner, Nguyễn Hùng Trương, was sent to a reeducation camp. Allowed to emigrate to the US in 1991, he returned just five years later.

I’d bet John Balaban bought anthologies of Vietnamese folk poetry at Khai Trí. Using Viets to translate, he presented his selection of ca daos as poems he had collected and recorded in the fields of a country at war. So fearless, this American. To bolster his lies, Balaban photographed eccentrically dressed followers of the Coconut Monk in Mỹ Tho. These weirdos were included in his anthology as “ca dao singers.” When I met Balaban in Carborro, North Carolina in 2004, he couldn’t speak one word of Vietnamese.

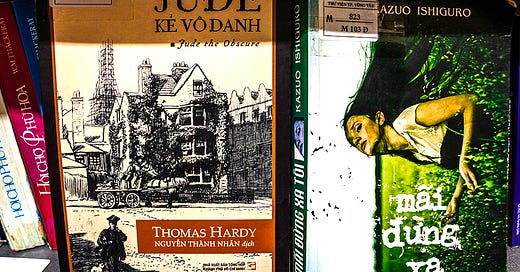

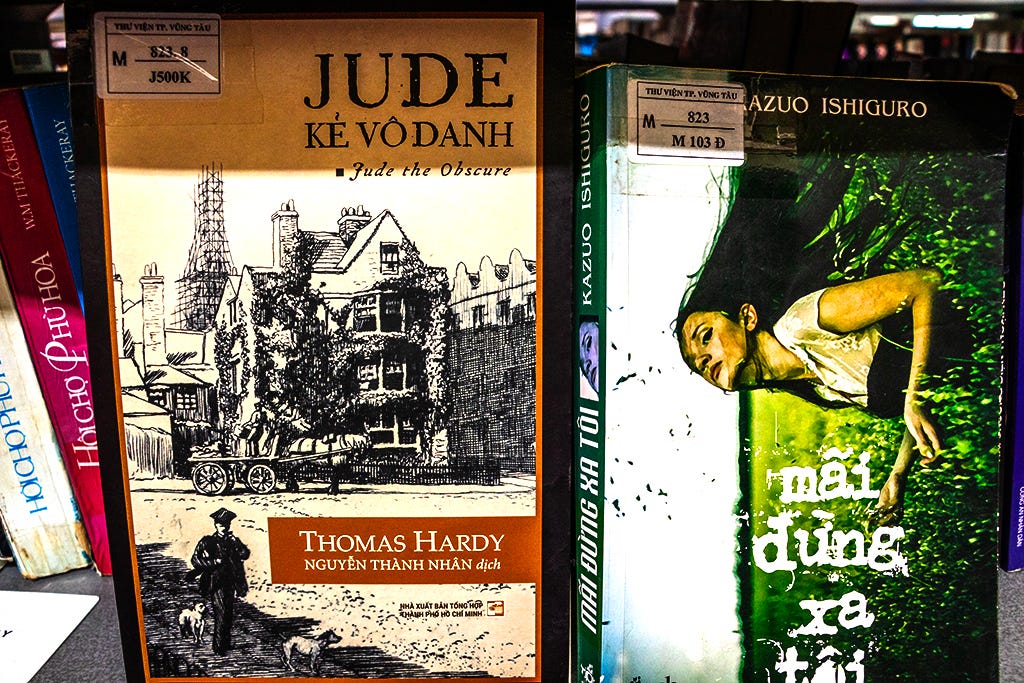

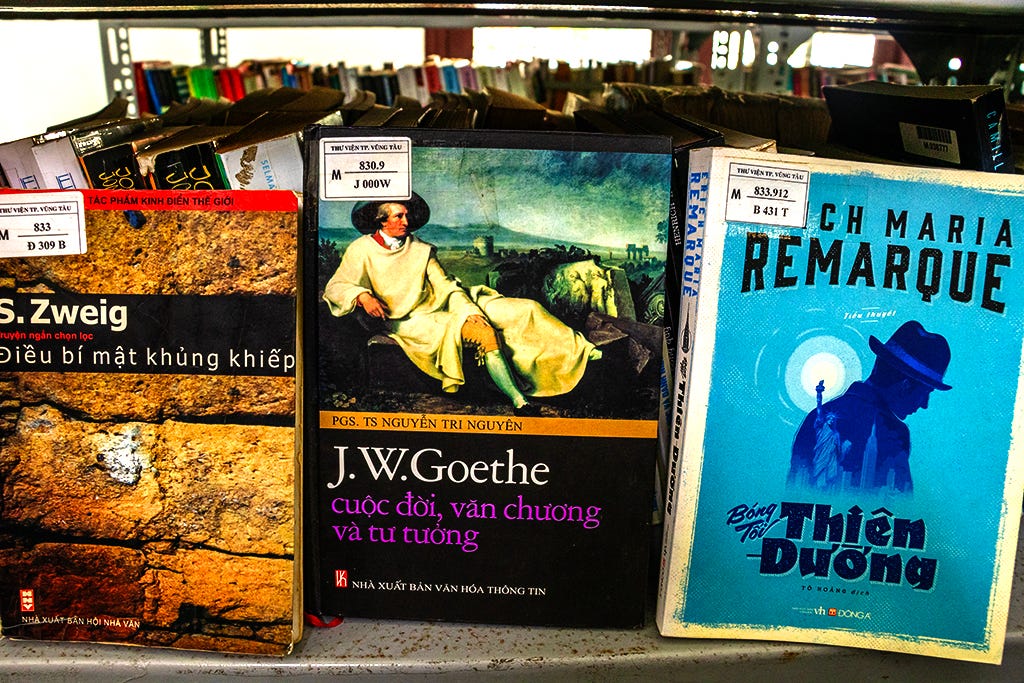

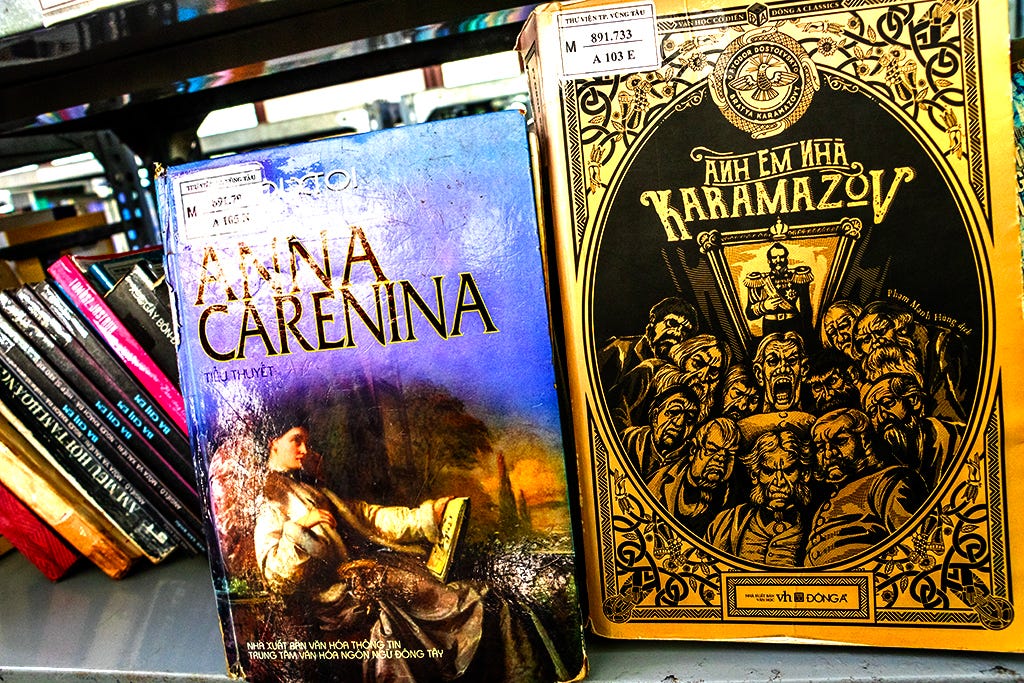

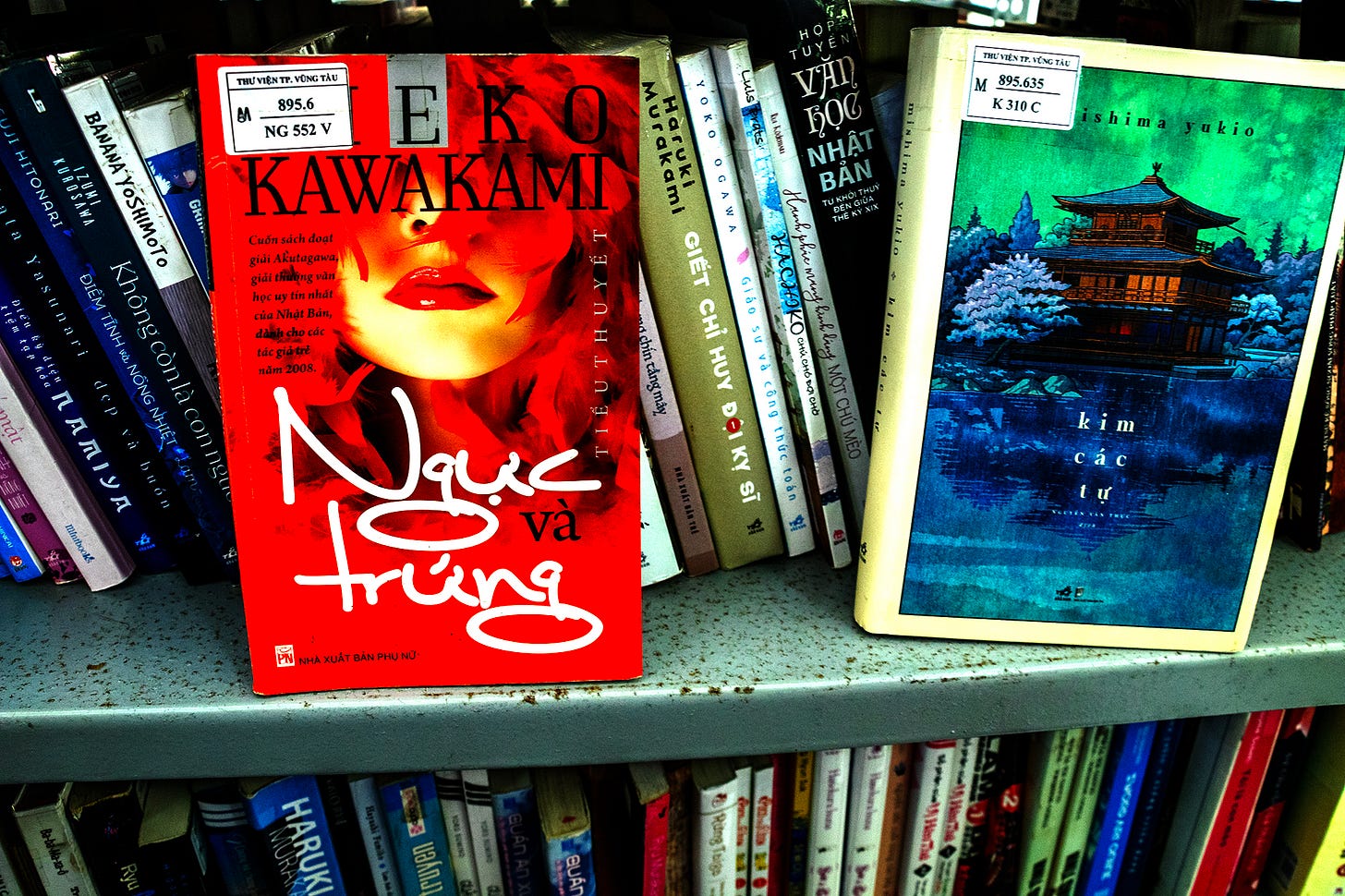

Like everybody else, I’ve gotten away from reading actual books. Yesterday, I finally went to the free library in Vũng Tàu. There, I was delighted to find translations of Kundera, Ishiguro, Steinbeck, Herodotus and my friend Mieko Kawakami. There’s a handsome collection of essays on Nguyễn Huy Thiệp. In 1998, we took the Staten Island Ferry so he could have a closer look at the Statue of Liberty. When I heard Thiệp say of NYC, “I don’t know how anyone can handle this chaos,” I immediately thought of Hanoi’s madness. In Maryland, he sketched me with a pen. Though seen in Hanoi years later, that drawing is probably lost. Entire libraries have disappeared.

After paying 20K [78 cents] for a library card, I checked out two books. This required a deposit of 150k [$5.88]. The librarian had gotten annoyed at my pulling out volumes to photograph, but I pointed out, for example, that José Saramago didn’t belong in the Japanese section, so I was helping her out. We made peace. From Nghệ An, she’s also a Đinh, so we’re like cousins.

Leaving the library after a couple hours, I felt an essential part of me had been recovered. In my late teens, I spent so much time in libraries. I also worked in the slide library of the University of the Arts. There, I shored up my knowledge of art history. My first published writing was art criticism.

Sharing the same floor with me at DC HomeStay is a niece of the great scholar, Nguyễn Hiến Lê. Browsing through his memoir yesterday, I found out he had spent much time at Saigon’s main library to improve his Chinese. Đào Duy Anh’s 1930 dictionary and George Cordier’s Grammaire Chinoise were his main texts.

Hiến Lê’s using a dictionary to teach himself made me think immediately of Malcolm X. Locked up in the Norfolk Prison Colony, Malcolm X decided, finally, he must deal with his ignorance:

I saw that the best thing I could do was get hold of a dictionary—to study, to learn some words […] I spent two days just riffling uncertainly through the dictionary’s pages. I’d never realized so many words existed! I didn’t know which words I needed to learn. Finally, just to start some kind of action, I began copying. In my slow, painstaking, ragged handwriting, I copied into my tablet everything printed on that first page, down to the punctuation marks. I believe it took me a day. Then, aloud, I read back, to myself, everything I’d written on the tablet. Over and over, aloud, to myself, I read my own handwriting. I woke up the next morning, thinking about those words—immensely proud to realize that not only had I written so much at one time, but I’d written words that I never knew were in the world. Moreover, with a little effort, I also could remember what many of these words meant.

Inspired by this, I taught myself Italian, sort of, with a Zingarelli Vocabolario della lingua italiana during 2002-2004. Staring at tabloids like Cronaca Vera, I had to look up just about every word. My fumbling around did yield translations of Marco Giovenale, included in Tempo: Excursions in 21st Century Italian Poetry. It also resulted in “Prisoner with a Dictionary,” in my Blood and Soap. Since Seven Stories Press hasn’t sent me a royalty check in years, I must assume that 1) None of my books are selling 2) Whatever I’ve earned is deducted by administrative costs. Whatever, man. I’m canceled.

Missing from the Vung Tau library are nearly all writers active in South Vietnam from 1954 to 1975. With few exceptions, those published overseas are also absent. There’s an endless information war in every nation.

On the facade of the Vung Tau library is that famous Cicero observation, “A room without books is like a body without a soul.” Though not one page of mine can be contained within, I fully expect a 12-foot-tall bronze statue to be erected by next week. That will teach the Nghệ An broad some respect.

Writers have been suppressed, jailed or even killed. Subject matters are perverted or ignored. My first book of stories, Fake House, was dedicated to “the unchosen.” In 2000, I wasn’t thinking about Jews or goyim. Then as now, I was drawn to whomever or whatever deemed unexceptional.

When I told poet Teresa Leo my second collection would be called Prosaic, she freaked out. That’s a horrible idea, she insisted, so I renamed it Blood and Soap. It is catchier. Sexiest, though, are still the unchosen with their prosaic lives, so I’ll keep sketching.

Roaming sellers of lottery tickets keep increasing. A newcomer at Cóc Cóc is a cheerful deaf mute who, just now, sold two tickets for 20k [78 cents] to Mai, the owner. Those slips of good luck the wordless woman tucked next to a ceramic Lord of Wealth seven inches tall. Sharing an altar with a thin moustachioed Lord of the Land, he faces a golden plastic toad biting a fake coin.

In Barcelona 22 years ago, I witnessed some middle-aged man in a rumpled suit kiss a lottery ticket before handing it to a customer. We all have reasons to be insane.

[Vung Tau, 2/18/25]

[Vung Tau, 2/18/25]

[Vung Tau, 2/18/25]

[Vung Tau, 2/18/25]

Bookstores and libraries are two of my favorite places. One nice thing about many of the independents is that they still welcome you to read stuff without buying it, as long as the book stays in shelf condition. Two places near here even have chairs to make it easy for you.

I spotted lots of familiar friends in those book photos. Obviously Vietnam does have well-stocked libraries, but what I guess I find most surprising is how very many books, from all over the world, have made it into a Vietnamese translation. This may be the best clue that many Vietnamese are avid readers--no one takes the time to translate most books into the languages of cultures not known to be widely literate.

You mentioned poetry translations. Verse is something I have to believe is much more challenging to translate than mere prose, since you need to capture the entire feel of it rather than just the literal meaning of the words. Perhaps the very grammar of the target language may not even support that. Some of the ancient Greek classics, my chief exposure to verse in translation, no doubt suffer from the effort--that is why there are so many versions, I guess.

I'm with what Troy says regarding learning languages. My English is excellent, but I've had schooling in 5 or 6 other languages in bits and pieces throughout my school days, and then later attempts to learn a couple myself--almost all for nought. In my early school days I was not a very serious student, so there's that excuse, I guess, but my later efforts were more dedicated. Despite all of it, however, I am essentially functionally illiterate in all of them, and can only lamely speak at the survival level in Mandarin. I remember Russian well enough to pronounce Cyrillic text, but no longer recall what most of the words mean. Looking back, I'd say (weirdly) that the Latin was actually the most useful for a number of reasons.

I had plenty of curiosity and, I think, incentive to learn them. The big problem lies not in the incentive, but in the opportunity to use them after you start learning them. It's not like riding a bike--you DO forget them if you don't exercise them regularly. My wife's nephew (a Mandarin, Japanese, and English speaker) knows this, which is why he asked me to have a weekly call with him for a couple of hours--he found his English was deteriorating because he wasn't using it enough.

Linh, first off, the photo of you and your friend Motoyuki Shibata is beautiful and peaceful. It captures a moment of better, pre-cancelled times. I enjoy this "Postcards" space not only for the literary nervous system of references but because it also affords a glimpse into the lives and backgrounds of the folks that comment here. I am but a prosaic, bumbling Columbo looking for clues at the scene of the crime, life's been good to me so far...haha. BTW is it "that comment" or "who comment?" Thanks Linh for helping us not feel so alone.