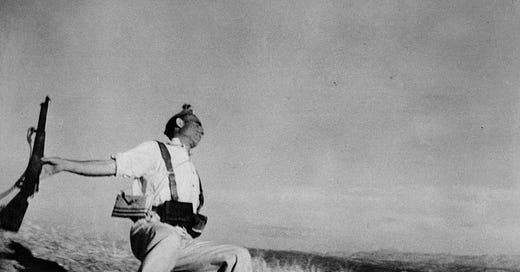

[Robert Capa’s Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death, Cerro Muriano, September 5, 1936]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is one of the world’s greatest, for sure. Of this 1936 photo, it explains:

Possibly the most famous of war photographs, this image is all but synonymous with the name of its maker, Robert Capa, who was proclaimed in 1938, at the age of twenty-five, “the greatest war photographer in the world” in the British magazine “Picture Post.” Taken at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War and showing the moment of a bullet’s impact on a loyalist soldier, this photograph has become an emblem of the medium’s unrivaled capacity to depict sudden death.

And here is the world’s most prestigious cooperative for photographers, Magnum Photos:

In his mid-twenties Robert Capa traversed Spain along with his partner photographer Greta Taro to document the civil war. Capa’s photographs of this time would bring him the status of the world’s “greatest war photographer”. The most iconic image of the Spanish Civil War—and indeed of Capa’s career—is the photograph of a Spanish Republican militiaman falling down wounded on the Córdoba front line.

Let’s hear from the man himself. In his only recorded interview, Capa said in 1947:

I had, once, one picture which was appreciated much more than the other ones, and I certainly did not know when I shot it that it was an especially good picture.

It happened in Spain. It was very much at the beginning of my career as a photographer, and very much at the beginning of the Spanish civil war, and war was kind of romantic, if you can see anything like that.

[“No, I can’t,” the interviewer interjects]

It was there, because it was in Andalusia and those people were very green, they were not soldiers, and they were dying every minute with great gestures and they figured that was really for liberty and the right kind of fight and they were enthused, and I was there in the trench with about 20 milicianos, and those 20 milicianos had 20 old rifles, and on the other hill facing us was a Franco machine gun.

So my milicianos were shooting in the direction of that machine gun for five minutes and then stood up and said “Vámonos!” and got out of that trench and began to go after that machine gun. Sure enough, that machine gun opened up and mowed them down. So what was left of them came back and again took potshots in the direction of the machine gun, which certainly was clever enough not to answer, and after five minutes again they said “Vámonos!” and got mowed down again.

This thing repeated itself about three or four times, so the fourth time I just kind of put my camera above my head and even didn’t look and clicked a picture when they moved over the trench. And that was all. I didn’t ever look at my pictures there and I sent my pictures back with a lot of other pictures that I took.

I stayed in Spain for three months, and when I came back I was a very famous photographer because that camera which I hold above my head just caught a man at the moment when he was shot.

There is so much bullshit in those three accounts. First off, it has been proven, from other photos Capa took that day, the falling soldier was not shot, with bullet or camera, at the Cordobá front line, but in Espejo, 30 miles away. Since there was no fighting in Espejo that day, he was probably not shot at all, not even by a sniper, as claimed by Willis E. Hartshorn, the director of the International Center of Photography.

Snipers don’t get too many chances to hit their targets. If you hear pop, pop, you get the fuck out of there. There’s no way in hell Capa was there to capture the exact moment a sniper’s bullet hit the exact man he had his camera aimed at, in a pretty damn good composition. I’m guessing his play partner had to flop several times for Capa to get that “classic” photo.

Capa himself said those milicianos were so green and stupid, they kept charging that machine gun, only to be mowed down repeatedly, so right there is a shameless lie. There was no machine gun blazing away in Espejo that day, Bob!

In 2008, though, distinguished war reporter Ron Steinman could still claim:

It is easy to attack the authenticity of any photograph, especially one made more than 70 years ago.

Unless Capa was a liar, and there is no evidence he was, I don't think it is necessary to doubt it. Keep in mind that Capa never made more of that photo than any other he took. There are those who can't let well enough alone so perhaps they will always doubt the authenticity of that photo

[…] Let that photo speak for itself.

Most photos don’t speak for themselves, Ron. Context or narrative, too often bullshit, matters a whole lot. Some guy in an astronaut suit may be said to be strolling or even driving on the moon. Starving prisoners at the end of a horrifying war are the “proof” of death camps, though, by definition, no one should be alive in any death camp to be liberated long after he has become useless for any task.

Staged photos has a long history. Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan arranged corpses for their Civil War photos. “A Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep,” for example, is actually of an infantryman who had to be carried 40 yards from where he was killed. That’s nearly half a football field.

In the high arts, we have people like Cindy Sherman, Joel-Peter Wikin and Jeff Koons, etc., but Jeff Wall’s Mimic (1982) is not appreciated the same way as, say, Garry Winogrand’s capture of a couple kissing, with a fat girl staring at the photographer in disapproval.

[Jeff Wall’s Mimic, 1982]

Though deception is a constant human instinct, don’t use that as an unlimited license. Introducing Capa’s lying interview, the International Center of Photography says “that Capa was not only clear, but highly articulate. His easy style underscores his innate proclivity for self-deprecation, humor, and storytelling.”

Capa didn’t show any “innate proclivity for self-deprecation,” for his claim that it was a blind and lucky shot is total bullshit. He didn’t “just kind of put [his] camera above [his] head and even didn’t look.” The 22-year-old staged this stunt to launch his career, and it worked spectacularly. He told a story, all right.

Like Elie Wiesel, Bob Dylan and even Barbara Streisand, Capa is a Jewish god, so he’s sacred in the West. Without that fake photo, he’d still be considered a first-rate artist, however. Plus, there are other great Jewish photographers, such as Weegee, Robert Frank and Garry Winogrand, etc., so let’s just admit Capa was also a weasel. With false modesty, he spun an elaborate yarn about his most famous image.

Although Capa’s Vietnam photos are among his least known, they include a handful of gems. His two photos of children crossing a Hanoi street in 1954 reveal the beauty, dignity and even sophistication of a society not yet plunged into war totally.

Snapping the boys, he positioned his camera very low, to make them monumental, practically, and equal in height to the French Foreign Legionaires in the background. He also noted they were singing. This fact adds to our appreciation, not just of the photo, but of Vietnam.

[Robert Capa’s French Soldiers waiting for children to cross the road, May 23, 1954]

[Robert Capa’s Members of the French Foreign Legion watching children cross the street, May 23, 1954]

For a month, I’ve written about deception, and last week, I even had a chance to write about it in the most personal terms. All this led me back to Capa.

On just his fifth day in Vietnam, Capa got off his truck to better photograph. Walking among soldiers, he was no point man, but in the middle, so seemingly safe, but a landmine snared his fate. Having staged death, he was now cast. A true artist, Capa was no timid creature.

In Leipzig, Germany on April 18, 1945, Capa photographed an American soldier freshly killed by a German sniper. Knocked backward, with his head at a painful angle, Raymond J. Bowman’s black blood spreads across the gray parquet floor. On a wooden chair with leather seat and curving armrests is an upturned helmet. In the back are leafless trees and iron curlicues atop a balcony wall.

Two years later, Capa cooly recalled, “It was a very clean, somehow very beautiful death and I think that’s what I remember most from the war.”

When Life published the photo on 5/14/45, it was titled, The Picture of the Last Man to Die. As usual with the press, it was nonsense, and Bowman was not identified. Seeing their dead 21-year-old, Bowman’s family recognized him, not by his face, which was obscured, but by the lapel pin bearing his initials. As for the last man to die, it’s supposedly Charley Havlat, who was killed on 5/7/45, but there’s no photo.

As for Capa, he’s probably the only Western journalist to die during the First Indochina War.

Tomorrow, May 25, is his death anniversary. Very rare, memorable art speaks for itself.

[Robert Capa’s last photo, taken seconds before his death on 5/25/54]

It is hard for me to believe that a Jewish photographer would use his art to lie about WW2. Fortunately we still have movies like Schindler's List and all those Holocaust survivor books to tell us what really happened.

In all seriousness, Capra's comment that he shot the photo without looking alone puts a lie to the authenticity of the photo.

It really is the case that everything we are told is a lie. That is why it is so hard for people to see the truth. It is too uncomfortable to believe that nearly everything they know is a lie. Doing so is bad for the ego and means you can't trust anything you haven't directly experienced so there is no simple solution.

In my younger years, I put a lot of credence in photo evidence, especially things like news footage. I always thought simply "seeing is believing." Pretty naive. Later, seeing reports and even footage showing how things like this can be (and often are) created or staged like CNN has been known to do cured me of automatically trusting such stuff.

Now, technology such as "deep fakes" and what seems to be an increased desire by the purveyors of visual media to mislead is making us less knowledgeable rather than more so. More's the pity. I guess we need to start looking at all of it first of all as creative art and fiction rather than as some kind of literal truth.

Anyone who has seen the movie "Fargo" might remember the text at the beginning saying that it was based on a true story. Later this was discovered to be a lie, but it is amusing to notice that it actually makes the movie more interesting to believe that it is so.