João Guimaraes interviewing Linh Dinh (part 1)

[photo from Britannica’s entry for Porto]

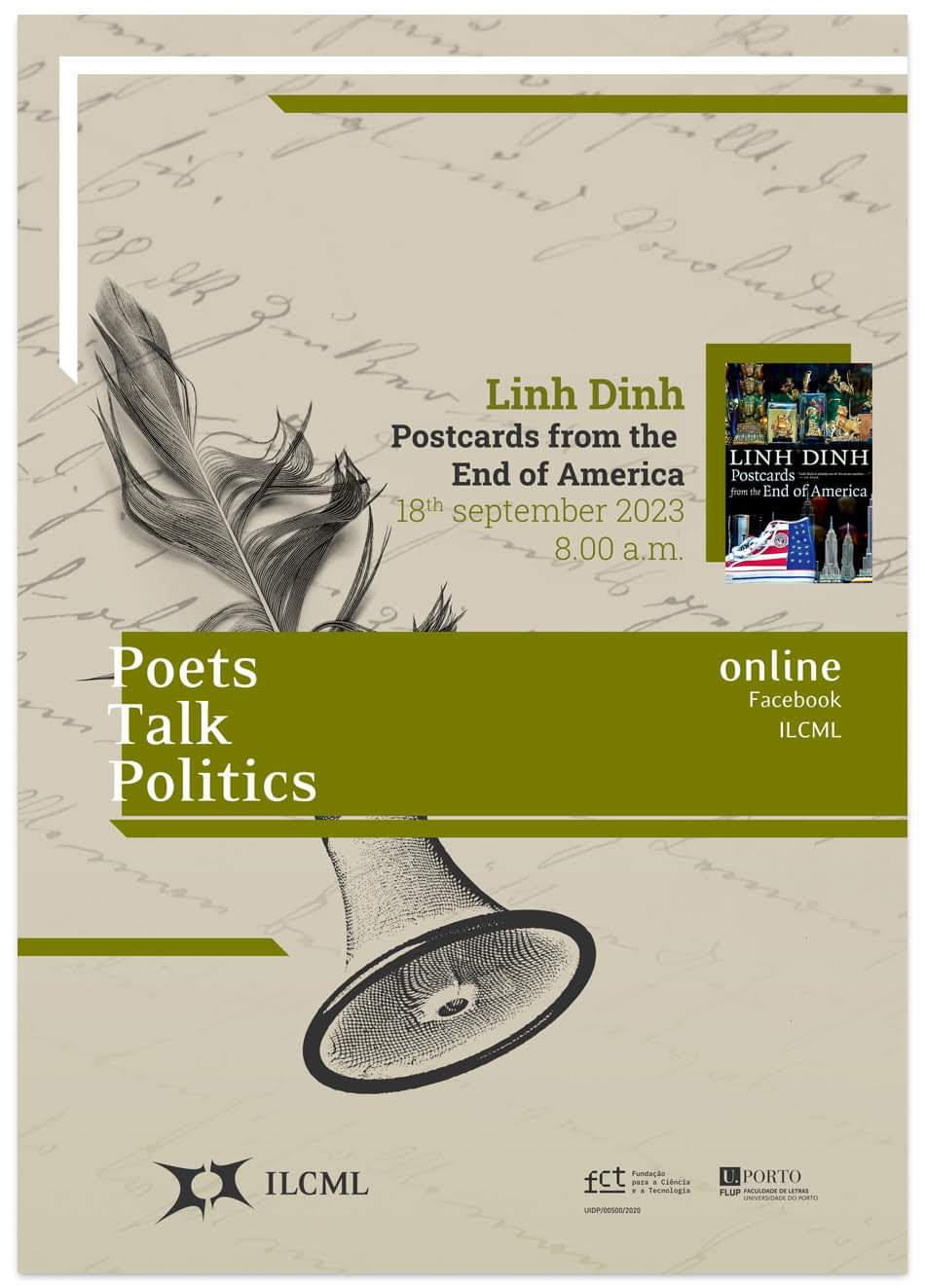

At my request, João sent me questions to prepare for our livestreaming conversation on 9/18/23, at 9AM, Portuguese time, at this channel: https://www.youtube.com/@institutodeliteraturacompa9632 . It’s a part of the University of Porto’s “Poets Talk Politics” series. Please note all the questions had substantial input from João’s students.

João Guimaraes: It seems to me that in your work a matter of “positioning” is always very significant — as we can see even by your SubStack intro, where there are several little marks of placement or displacement (Before being canceled, I was an anthologized poet and … Now, I write about our increasingly sick world for a tiny audience … Drifting overly much, I’m in Cambodia). And positioning understood in more than one way, not only politically, but even in a physical or geographical sense. At the beginning of “Postcards from the end of America”, for example, there is a section where you write about riding buses. The very word “Postcards” emphasizes the importance of place. Also, in a 2022 interview, you talk about some writing classes you gave and how you used to encourage students to go where they didn’t belong, to take the subway and get off at unknown stops. And today, of course, you are in a very different space than the one you used to inhabit before. So, at the risk of being too broad with this question, could you discuss these ideas of “positioning” and “place”, especially how it relates to your career and your writing over the recent years?

-Your average man in Lebanon does not think like one in Israel, Germany or Singapore. Even in a single city, place dictates much. In Philadelphia, you can go three blocks and be in an entirely different universe. Though we may know this in theory, it’s helpful to experience it firsthand. The reality of South Africa, Albania, Cambodia or France, etc., is never what you expected. Further, each place becomes more complex and interesting the more time you spend in it. Even staying in just one city for decades, you should challenge or force yourself to discover parts unknown. Out of laziness or fear, most people won’t get out of their cloistered comfort zone, which is fine, for they have enough to deal with, just surviving. After another long day, they just want to duck into the same tavern to get even more glazed eyed. For a writer or self-styled thinker, though, the dread of actual experiences, especially unscripted ones, is usually fatal.

Born in Saigon, I lived in four different houses. At age 11, I was a refugee, with Guam my first stop, then Arkansas. Settled in the US, I spent at least a year in four different states before entering college. In each of those states, I lived in more than one house. From early on, displacement shaped and informed me. As an adult, I’ve spent at least three months in ten countries, and have visited many more. Almost never driving, I walk, so I can measure each place with my slow moving body. Wandering, you catch more, good and bad.

I would like to ask you a question about “process”, be it of writing or thought. There is a thematic concern in your most recent writing and interviews (at least I think there is) with the idea of “truth”: revealing, denouncing, exposing… How much of this is conceived ahead of time? Do you discover things while writing and does writing change your perceptions. or is writing mainly a way to divulge information?

-Writing essays, you’re bound to be polemical, but what’s left of the poet in me still introduces more slippery elements. It’s a moral imperative to chase and tease out the truth, no matter how shadowy or ambiguous. Since the tendency to lie or dissimulate is so widespread, we must start by fighting it within ourselves. Talking or writing, are you trying to get closer to the truth, or are you bullshitting? Most people opt for the latter because they have some hidden agenda or are just fearful. Since even the most banal truths can terrify, most people prefer to cloak themselves in layers of slimy lies.

Writing is thinking made concrete. Revising and deleting, you don’t just finesse, but discover. To quote Eliot, “That is not it at all. That is not what I meant, at all.” I think he also said, “For something said, something else must be said.”

A writer should be his best reader. This is actually a foregone conclusion, since most writers are very badly read. Since we can’t even understand ourselves, how can we adequately grasp any piece of literature, much less a genuine writer?

Rereading myself is a painful experience. I should have said this or that differently, or added much more. Alone in my room or walking down the street, I sometimes blurt out, “You’re a fuckin’ idiot!” To poet Nguyen Quoc Chanh, I asked, “Doesn’t everyone do that?” “No, I think you’ve gone mad,” he answered. I will insist, though, that everyone should often scream to himself, “You’re a fuckin’ idiot!” The world would be a much better place.

A question about the idea of authorship (the “I”) in your texts. Is the I basically a character? How accurately does it represent you, or at least how do you see this transposition of your personality and ideas into your writing? Moreover, how does that transposition change according to the format in which you are writing (poetry, short stories, a more hybrid journalistic mode)?

-With fiction, the I is often fictional. With poetry, it’s generally assumed the poet is speaking as himself, but this needs not be the case, at least not literally. My poems tend to be fictional, even fantastic, so what’s depicted or said must be read metaphorically or poetically. It’s obviously untrue that “my name, that of a ballyhooed scholar, from the 23rd century (AD or BC, I can’t remember),” can be found on “the next-to-last stele at the Temple of Poesy” in Hanoi. The I here is speaking about himself as a man long dead or not yet living. In the story, “The Ugliest Girl,” the I is clearly not me, but she’s me deep down, and you, too, and perhaps more so than she’s me. We are the ugliest girls.

Each of us is merely a vehicle, or path, if you will, towards some dim understanding. A writer’s job is not to express or describe himself, but to use himself, in the most ruthless way possible, as an instrument to depict as much of the world as possible. The I shouldn’t be some egotistical complainer but a voracious eye.

Whitman’s I was more virile and voracious than the actual man, but he wasn’t boasting. America’s greatest poet created a vast I to draw us timid souls into this unspeakably fantastic world, and not as hedonists, I don’t think, but worshippers. Like us, Whitman mostly just ogled, but at least he wasn’t staring at screens. We are beyond miserable. Like a camera, Whitman was a promiscuous voyeur.

You have positioned yourself against the way affirmative action in the United States unfairly deprives talented people from entering universities. You also suggest that despite being given special treatment, African-Americans are nevertheless disproportionately involved in crime and in struggles with the police. The issue of “victimization” is also raised in your posts. Do you not agree, however, that African-Americans have over time suffered more discrimination than other minorities and that this cycle of oppression/exclusion continues to put them at a disadvantage vis-à-vis people from other races in the United States?

-Affirmative action doesn’t just affect university admission, but government contracts and jobs.

Affirmative action is judging people based on race, which is the very definition of racism. The unfairly treated race or races will react with racism of their own, because racism breeds racism. In the US, this racist policy is applied so mechanically that a Chinese billionaire who’s a recent immigrant, say, can procure a minority contract over an impoverished ethnic Albanian, because the latter is white. A man who is 1/8th black also qualifies as a minority, so he, too, can snatch a government contract over an Appalachian white who’s been poor for ten generations, and whose ancestors came to the US as indentured servants. Affirmative action also taints and stigmatizes the achievements of favored races, because you’re more likely to think a black professor, policeman or fireman, say, only got his job because he was black. That’s very unfair to a genuine black achiever.

Instead of saying black Americans have suffered more discrimination than other minorities in the US, I’d term it exploitation and abuse, which always happen to the weaker of two parties. This doesn’t mean, though, that the weaker man is any less aggressive or evil. He’s just weaker.

In Africa, you have stronger blacks exploiting other blacks, Arabs exploiting blacks, then whites exploiting Arabs and blacks. Now, some people are saying the Chinese are exploiting Africans, but let’s see how that plays out.

The real quandary here is the inequality between races, nations or any two people. Between you and me, someone must be taller, stronger, smarter, better looking and so on. If you’re inferior to me in every way, you must cope with it the best you can, and since I’m tempted to exploit and abuse you to the maximal extent, the law should step in to prevent the worst. What the government shouldn’t do, though, is to give you a degree or job you’re not qualified for, and it’s certainly a gross injustice should you be hired over me.

There are so many ways to measure anyone or anything, though. I’ve spent +6 months in Laos. The people here are poorer, shorter and have a lower IQ than all their neighbors, and yet, Laos is a marvelous country, with the most pleasant people, so they definitely have something over, say, Vietnamese, Cambodians and Thais. It’s probably not measurable.

On 3/1/18, the South China Morning Post published, “A Chinese condom manufacturer says it is considering making its products in different sizes after Zimbabwe’s health minister complained that contraceptives made in China and exported to the African nation were too small for its men.” That’s not racism. We’re not equal.

In Namibia last year, I met an Angolan who bragged about how easy it was for him to bed local women. It’s because “Nigerians, Zimbabweans and Angolans all have huge dicks,” he said, with his province, Cabinda, especially famous for this.

The image of food and the act of eating or even devouring seem to be of great significance in your poetry. It might be related to social critique like in “Eating fried chicken”, to dynamics of power like in “Nativity”, or to cultural difference and confrontation like in “Earth Cafeteria”. It’s never a feast, but rather a practice of dominance/obedience. Could you please talk a little bit more about the image of food in your poetry?

-In “Body Eats,” I show how Vietnamese use “eat” to convey just about anything, as in ăn khách [eat customers] to mean your business is doing well. To decisively defeat someone is to ăn sống [eat raw]. So central to our existence, eating is nearly synonymous with it, but eating isn’t just a fact, but process, so I also deal often with shit as an annoying fact and metaphor. I’ve pointed out how shit is constantly uttered in American English, as if something so hidden must be evoked endlessly. With shit much more visible in a collapsing USA, shit will fade from American lips, but this will take time.

Food is also our most democratic heritage, unlike literature, art or even history. What you and your ancestors eat make you distinctive from even your nearest neighbors. Again, we’re not the same, and should never be. Within the last half century, there arose a tiny, supposedly rootless tribe who claimed they could be at home anywhere, so could eat anything, but this is nonsense. I’ll use myself as an example. Though I’ve eaten dog, cat, field rats, various insects, the stinkiest cheeses, American cheese, fermented shark, jellied eel, raw lamb, turkey bologna and poutine, etc., I cannot claim to have enjoyed all of them equally. That’s impossible, not just for me but anybody. Our food preferences, then, define us.

In some of your interviews and in the book “Postcards from the End of America” you refer to poor people as your people. Do you think that there are any other ways to develop solidarity except sharing life conditions, social, economic or migration background? In your opinion, is solidarity all that it takes to portray the other in a respectful and a truthful way?

-Making very little money, I was a filing clerk, house cleaner, housepainter and window washer. After I became an author, I would be invited to teach at this or that university, but these jobs were only temporary, so I never entered the middle class. I never had a credit card or a house, and I’ve only briefly owned two used cars. I must clarify that my relative poverty was mostly voluntary.

(My “Clean, Clean, Clean,” published in Harper’s, is an account of me as a house cleaner. I didn’t submit the poem. The editor found it somewhere.)

A college drop out, I wanted to devote as much of my time as possible to writing and painting. Before I gave the latter up, I showed in galleries and wrote art criticism. I was critic-in-residence at Art in General in NYC, and I guest-curated a show at Moore College of Art in Philadelphia.

Though vaguely an intellectual, I hung out with those who frequented the cheapest bars. That said, I think everyone should be interested in how people get by. The degree of physical, mental and psychic strength it takes to be a factory worker, line cook, dishwasher, waitress or car mechanic, etc., borders on the superhuman, especially in a highly efficient, read exploitative, society like America. So no, you don’t need to be of the same background as anybody to relate to him. Just be curious and listen. Before being canceled, I had submitted to Seven Stories Press a manuscript called Obscured Americans. It’s a series of long interviews of the most ordinary people. All their stories, though, are astounding and often harrowing.

Note: The time on the poster is wrong. It will be not be at 8 but 9AM, Portuguese time.

Linh's analysis and description/explanation of Affirmative Action is the best I have ever read. Linh speaks the absolute truth about what affirmative action really is and what it amounts to.

Thank you, Linh, for speaking out the truth of it.

Hi PhilH,

He's a professor at the University of Porto in Portugal.

Linh