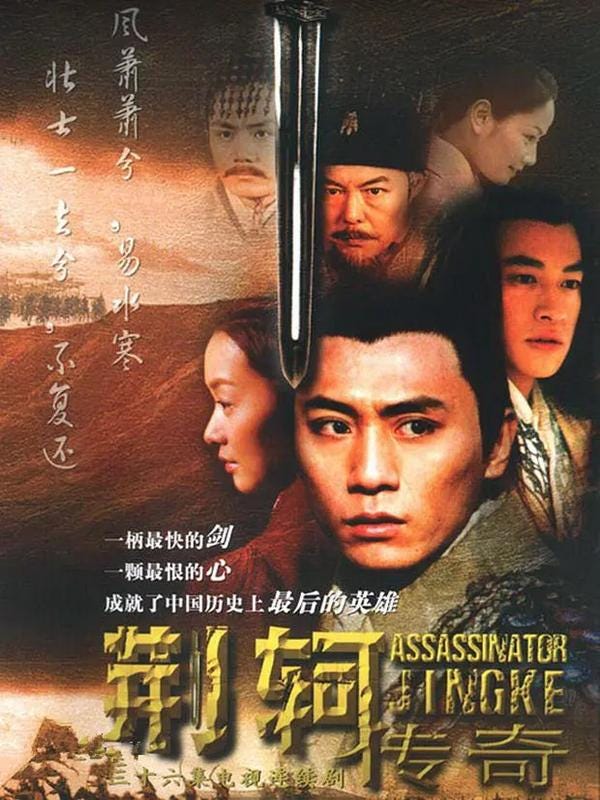

[Liu Ye as Jing Ke in Raymond Lee’s 2004 TV series, Assassinator Jing Ke]

Writing for an English speaking audience, the title of this article is the opposite of a click bait, so how many readers do we have left? Three? Four? Whatever.

These characters are Chinese from the 3rd century BC. All extraordinary, they’re immortalized by Sima Qian (c. 145-c. 86BC) in his Records of the Grand Historian.

Sima Qian tells great stories. Burton Watson, “Early Chinese historians, pedagogues in the broadest sense of the word, have made full use of the anecdote, developing it to a level of complexity and literary subtlety far above its Western equivalent, exemplified by such stories as that of Alfred and the cakes.”

While Alfred and the cakes is suitable for UK preschoolers, Sima Qian’s tales are for the most philosophical and reflective adults. The issues they raise will always intrigue and baffle men.

Yevgeny Prigozhin has just been killed. Though he never threatened Putin directly, he did more than enough to incur the Russian leader’s wrath. Drunk with power and attention, Prigozhin miscalculated his place, thus vulnerability, within the larger picture. Still, we don’t know who just silenced him. It’s too simple to dismiss Prigozhin as some foolish footnote. Like Jing Ke and so many others, he was bold, and that’s not nothing in a world of cowering men.

Introducing Jing Ke, Sima Qian relates seemingly trivial incidents to adumbrate his character. A man may expose himself with a single word, gesture or look. Though learned, Jing Ke was also martially inclined. Discussing swordsmanship with Ge Nie, Jing Ke was offended when he was glared at, so abruptly left. Playing a board game with Lou Goujian, Jing Ke didn’t appreciate being shouted at, so he took off. In yet another city, Jing Ke became chummy with a dog butcher and Gao Jianli, a lutist. Each day, they would get trashed together at the market. As Gao Jianli played, Jing Ke sang. So moved by their tunes and booze, they would sob as if no one was around.

China then was as fragmented as Greece before the League of Corinth. Because he was exceptional, and saw himself as such, Jing Ke could move from state to state and be well received by its best men, not just dog butchers. While dallying in Yan, Jing Ke was presented with his destiny.

Having endured for eight centuries, Yan was no joke, but now it was seriously threatened by the invincible Qin, whose ruler would bequeath us the Great Wall and 8,000 life-size and individualized terracotta warriors guarding his tomb.

To save Yan, Crown Prince Dan sought the counsel of Tian Guang, but the old man said his mind was no longer sharp, so recommended Jing Ke. Please arrange this, the Crown Prince begged. As Tian Guang was leaving, the Crown Prince asked him to keep their conversation confidential. This didn’t go well.

Keeping his word, Tian Guang told Jing Ke to go see the Crown Prince, then he did something incredible, if only to us 21st century wimps with no sense of honor. Offended that the Crown Prince didn’t trust him completely, Tian Guang slit his throat. Dead, he wouldn’t talk, so the Crown Prince needed not worry.

To Jing Ke, the Crown Prince said an exceptionally brave man was needed to approach the King of Qin under some pretext. Playing to the vagabond’s vanity, the Crown Prince said Jing Ke was perfect for the job, then he flattered Jing Ke further by lodging him in grand style. Gorgeous women were provided, and exotic gifts brought over days, yet Jing Ke had no solution, so the Crown Prince finally said, “Since Qin troops are about to cross the River Yi, I can’t go on serving you like this even if I want to.”

Showing his genius, ruthlessness and suicidal impulse, Jing Ke reminded the Crown Prince he had in his territory an ex Qin general, Fan Yuqi. Since much gold and territory were offered by the King of Qin for his head, why not use that to gain entry into the Qin palace? No, the Crown Prince firmly replied. It would be dishonorable to kill a man he had given refuge to.

On his own, Jing Ke went to Fan Yuqi. Due to his falling out with the King of Qin, his entire family, including his parents, had been killed, Jing Ke reminded Fan Yuqi. Weeping, the old general admitted it hurt him to the bone marrow. Revenge was possible, though, if you would give me your head, Jing Ke said. Presenting it to the King of Qin, Jing Ke could stab him in the heart, “but surely, you’re not willing?” Au contraire, Fan Yuqi slit his throat right in front of Jing Ke. Maybe Orientals are crazy.

With coveted head in pretty nice box, Jing Ke procured the best dagger possible, then had it coated with poison. Testing it, he instantly killed several people even if the wound was most superficial, with just a thread of blood. This dagger, he would hide in a scrolled map of Yan. With two prizes for the King of Qin, Jing Ke enlisted a 13-year-old murderer. Nearly ruining their plan, this boy would tremble with fear inside the Qin palace.

Crossing the River Yi, they were sent off by a small party dressed in white, the color of mourning. Never turning back, Jing Ke left behind this couplet, “The wind softly blows, the water is cold / Gone, the strong man won’t return” [“風蕭蕭兮 易水寒 / 壯士一去兮 不復還”].

Since the King of Qin became Qin Shi Huang, the great unifier of China, Jing Ke obviously didn’t succeed. One may even ask if his assassination attempt was wrong headed or petty? Missing his target at close range, he would be slashed eight times by the King of Qin, before courtiers finished him off. Perhaps Ge Nie had reasons to glare at this proud man. Jing Ke’s thinking on swordsmanship may not have been all that.

With volcanic wrath, the King of Qin set out to conquer Yan, but this took five years. Since all those associated with Jing Ke were ordered killed, Gao Jianli the lutist had to go into hiding. Working as a servant, he exposed himself, however, by commenting on others’ lute playing. Asked to play himself, Gao Jianli astounded everyone, so eventually, even Qin Shi Huang demanded his service. When the emperor found out his identity, he merely put out his eyes. Not appreciating this act of mercy, Gao Jianli plotted his revenge. Filling his lute with lead, the blind man tried to whack the emperor on the head, but, like Jing Ke, he failed. Had either man succeeded, he would have been killed anyway.

What do our characters have in common? Motivated by revenge, pride or, simply, love of music, each couldn’t help but be himself, even if it cost him his life. Sima Qian concludes that those who are resolute and true to themselves deserve to be remembered.

Of course, most men would not have been so rash, bold, proud or true to themselves. As weasels, we read such tales with amusement, if not contempt, for we would never be so stupid as to risk anything, for anything. It’s best to keep your head down for another mess of baked beans. Others can die. There are so many of them. Pain hurts, so who wants it? One more second of life, no matter how abject, is worth more than the greatest posthumous fame.

[Pattaya, Thailand on 1/17/23]

[Busan, South Korea on 5/3/20]

[Pakse, Laos on 8/25/23]

[Busan, South Korea on 6/6/20]

The Warring States period in Chinese history is fascinating and complex. It is still impressive to consider that in the 3rd century BC, when most of the planet was still sleeping rough and running around in animal skins, this advanced, literate, philosophical culture that had built extensive permanent works already existed.

A great and entertaining entree into this history for those who aren't immediately inclined to find a decipherable book on the subject is to watch some of the excellent historical costume dramas that Asia has produced on these themes. These often motivate my curiosity enough that I find good books on the subject afterwards to learn more, and to see how much was actually true. Asian producers are much more faithful to history, at least in broad outline, than Hollywood. I have a real gripe with the way Hollywood often warps history to serve modern-day (often trivial) political narratives. When I read up on Asian history after watching an Asian-produced drama, I find that they don't warp history in such obvious ways, if at all.

One show I really liked on the above period is the Chinese-produced "Qin Empire" that can be found on Netflix. It is very long and detailed (and you have to read subtitles, of course), but as far as I can tell, faithful to the recorded history. The three seasons cover the century leading up to the final unification of the states under Qin. If you're still thirsting for more after 200-odd episodes when you reach the end, you can watch the earlier-produced show "King's War" that covers the period between unification and the dissolution of Qin and the passing of the baton to Han.

I have also watched numerous historical dramas produced in Korea (one of the most famous in "Jumong"), and then there is the Turkish-produced "Ertugrul". An interesting feature of all these is their effort to leave the domestic viewer with a sense of pride in his history. I am neither Chinese, Korean, or Turkish, but I can feel it. When was the last time you noticed this in Western programming, which if it evokes any feeling about our history, seems designed to make us ashamed? Propaganda and narrative are at work everywhere and always in the modern state.

But every empire can find both pride and shame in its history if it looks objectively. At the beginning, empires do what they decide they must to make life good for their own citizens. The signal that you are nearing the end of empire is when State power begins to turn itself inward against its own citizens.

Brilliantly evocative writing and photos, Mr. Dinh. Thank's for the thought provoking images.

I find that most advertising in The States (to change the subject slightly) is aimed at nine or ten year olds (of any age). The ads feature people not just smiling but grinning from ear to ear conveying to the viewer, "you could be having the good time I'm having if you just consume the product I'm consuming." What a sad, infantile distorted view of life we are subjected to here.

America is a nation now based on images and slogans. The superficial image; the trite sound-bite. It seems to me that a lot of our fellow citizens are discontent if they aren't constantly having the carefully crafted faux good-time they see in advertisements.

So thanks for seeking the truth and avoiding the trite. There's more to life than "have a nice day!" Or is it just me?